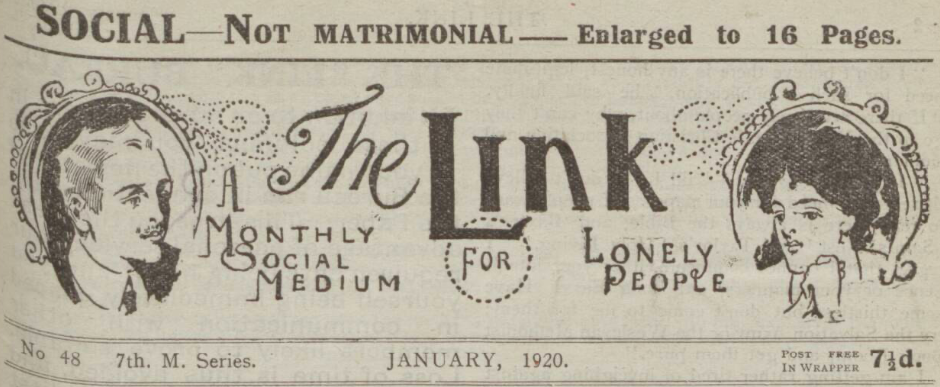

A Monthly Social Medium for Lonely People

Before the days of Tinder and Grindr, there was The Link. A lonely hearts publication which allowed members of the public to reach out for friends or pen pals by placing a classified advert of twenty-five words or less. Published monthly in London between 1915 and 1921 (known as Cupid’s Messenger during its first year), it also acted as a means for homosexual men to discover each other and make contact. At a time when homosexuality was illegal, this was of course risky business. Classified ads in these instances were written in a covert manner, with a coded language we could say, to avoid raising suspicion.

Where the majority of ads took the format of ‘young male seeks girl of similar age’, ‘gentlelady seeks gentleman’, or where males were seeking genuine friends of either sex, numerous adverts also appeared for same-sex connections only. Two examples of genuine same-sex requests from November 1919 and August 1920 respectively, include ‘Gentleman (London, S.E.), seeks correspondence same sex with view to friendship. Special interest in music and literature’, and ‘Young Fellow (London, N.), 21, wishes to meet another about same age, view friendship’. Here, the direct nature of both adverts, clearly indicate platonic interest. In contrast, in terms of male requests for possible same-sex romantic associations, one such advert from the January 1920 issue reads:

Young Gentleman London (N.W.1), 24, musician, cultured, artistic, intellectual, lonely, and unhappy, seeks unconventional, broadminded male chum, same age and tastes. Warm, sympathetic friend.

Whilst one could say this advert is completely innocent and purely refers to a normal friendship, the use of the words unconventional and broadminded suggest a connection beyond the heteronormative, and warm and sympathetic allude to the caring and romantic. Together, they carry a secondary and covert meaning for homosexual interest, without actually referring to a same-sex romantic attachment. Another example from September 1920 is:

Young Man (London, S.W.), 22, artistic, musical, desires companion, own sex, same age and temperament.

The choice of the word companion is interesting here, as opposed to chum or pal which are both in frequent use throughout The Link. Companion suggests a more solid and permanent form of relationship, and certainly hints at something more than friendship. Also on the same page:

Bachelor (London, N.W.), 44, educated, good appearance and position, very lonely, lived abroad years, wishes meet other gentlemen 44-70. Real friendship given.

Here, although friendship is clearly offered, using the term bachelor in the context of a lonely hearts publication with a request to meet other gentlemen, again alludes to something more than platonic friendship. Several words start to become repetitive in adverts of this type throughout The Link, which include unconventional, artistic, musical, affectionate, and sympathetic. These words, when in combination with each other or with terms such as companion, form the coded language.

In The Link therefore, we have clear indications of classified adverts being placed by homosexual men, albeit in a covert manner. The result of such ads did not go unnoticed. A court trial which took place against the publication in 1921 accused its proprietor Alfred Walter Barrett of corrupting public morals; along with William Smyth of Belfast, Geoffrey Smith of Enfield, and Walter Birks of Carlisle. On the arrest of a separate crime, Birks was found in possession of love letters from Smyth, and Smyth subsequently found in possession of correspondence of an explicit nature with Birks and other individuals, including Smith. The Birks and Smyth relationship was discovered to have started through an introduction via The Link. Fifteen separate charges were made of conspiring to corrupt public morals ‘by introducing men to women for fornication and by introducing men to men for unnatural and grossly indecent practices’, along with the men being ‘charged with aiding and abetting the commission of gross indecency and conspiring to enable the commission of such acts with others unknown’. The eventual outcome was two years hard labour for all four men with the judge passing the most severe sentence possible.

In essence, this case demonstrates the absolute severity of the law where homosexuality was concerned before its partial decriminalisation in the United Kingdom in 1967. Hence we see why there was a necessity for covert methods such as a coded language, for homosexual men to recognise and meet each other before this time.

Sources

The Link – November 1919, January 1920, August 1920, and September 1920. Available to view from the British Newspaper Archive.

Cocks, H.G. (2002). ‘Sporty’ Girls and ‘Artistic’ Boys: Friendship, Illicit Sex, and the British ‘Companionship’ Advertisement, 1913-1928. Journal of the History of Sexuality.

Daily Mail (1921). ‘Link’ Sentences. Daily Mail, 11 June 1921.